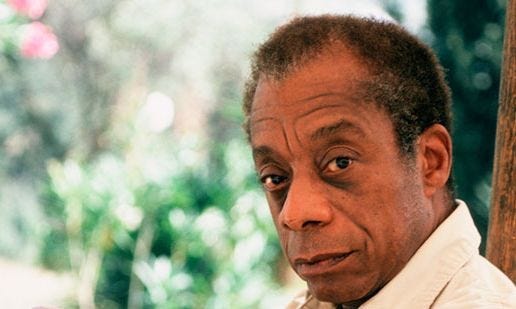

Reflecting on the Fire — Remembering James Baldwin on His 100th Birthday

“I am saying that a journey is called that because you cannot know what you will discover on the journey, what you will do with what you find, or what you find will do to you.”

— James Baldwin to Jay Acton (Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro 5)

One hundred years ago to today — August 2, 1924 — God gifted America its greatest literary talent. A man who left his mark as one of the nation’s greatest essayists, who was a witness to the great social and political movements of the mid-twentieth century, and whose vast library of work continues to strike modern audiences for how clearly and poignantly it describes the matter of race relations and civil liberties to this day. I am, of course, speaking of writer, commentator, and civil rights icon, James Baldwin.

Baldwin was born on August 2, 1924, in Harlem, New York. At the age of 24, distraught by the racial climate in the United States, Baldwin went to Paris where he underwent work as a published book reviewer and — after ten years of work — published his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain in 1953. He continued his literary work, writing a series of essays that would then be published in Notes of a Native Son in 1955.

To describe the timeline of Baldwin’s entire bibliography in detail here would be an exhaustive ordeal. Throughout his career, Baldwin published 6 novels, 9 short stories, and an overwhelming amount of essays, poems, and letters, both assembled and not assembled, across over half a dozen volumes. To collect — let alone read — the totality of Baldwin’s complete works is a feat in itself, and a worthwhile one at that.

Baldwin continues to resonate with modern readers as he has identified and articulated what figures, like W. E. B. Du Bois and Barack Obama, have stated is the definitive throughline of American culture and politics: the nature of the color line.

Baldwin establishes this clearly in his essay, White Man’s Guilt:

“No curtain under heaven is heavier than that curtain of guilt and lies behind which white Americans hide.

…The American curtain is color.” (Baldwin, The Price of the Ticket 416)

Baldwin found the language to define, in specific terms, the roots of America’s racial divide. In the remnant notes that would become the documentary I Am Not Your Negro, Baldwin states that the origin of white hatred is terror. He describes it as “a bottomless and nameless terror, which focuses on this dread figure, an entity which lives only in his mind” (Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro 60).

In contrast, Baldwin declares that the origin of black hatred is a form of rage. This rage that Baldwin describes, however, is not one directed at white individuals. It is not an anger towards the objective figures of whiteness, but instead a frustration at outside interference in the lives of black people. Baldwin says that the black man “does not so much hate white men as simply wants them out of his way, and, more than that, out of his children’s way” (I Am Not Your Negro 60).

It is these dueling animosities between two segments of the American population that formed the foundation of the social and political divides that defined Baldwin’s time; it is those same forces that define our divides today. American history and any notion of democratic progress have been met routinely with a societal backlash from the very forces that seek to drive these coalitions apart.

Baldwin assessed that “one can measure very neatly the white American’s distance from his conscience — from himself — by observing the distance between white America and black America” (The Price of the Ticket 416). Baldwin’s use of the term “conscience” is paramount to his argument, which he presents in his entire bibliography. At the core of this conflict, what Baldwin describes as “the Negro problem,” is an inability for American citizens to face their private selves, to reflect on why there must continue to be a dependence on the notion — conscious or otherwise — of a racial hierarchy (I Am Not Your Negro 56).

It is incumbent on each of us to call attention to such biases where they exist, lest we fall prey to the same traps that have ensnared this nation since its founding. Baldwin believed that what is perilous for one race is as deadly for the other:

“…if black people fall into this trap, the trap of believing that they deserve their fate, white people fall into the yet more stunning and intricate trap of believing that they deserve their fate and their comparative safety and that black people, therefore, need only do as white people have done to rise to where white people now are.” (Baldwin, The Price of the Ticket 415)

And so in the face of such adversity, in the presence of a collective national trauma that has impacted generations, what cause is there to hope? How are we to move forward?

Baldwin opens The Fire Next Time with a letter to his nephew (also named James) where he advises the young child to not give in to those outside forces that conspire to make him feel small. It is here that Baldwin believes he has found an answer to our societal dilemma.

Drawing from his background as a former Christian preacher and the philosophical teachings of Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, Baldwin proposes that we answer profound hate with radical love.

In this letter, Baldwin says to his nephew and, by extension, to us:

“…I know how black it looks today, for you. It looked bad that day, too, yes, we were trembling. We have not stopped trembling yet, but if we had not loved each other none of us would have survived. And now you must survive because we love you, and for the sake of your children and your children’s children.” (Baldwin, The Price of the Ticket 339–340)

It is in this passage that Baldwin stresses that our very existence in this life is a manifestation of a love and compassion for one’s fellow man that persists despite adversity and generational trauma. In one of my favorite interview segments, Baldwin expands on this theme:

“I can’t be a pessimist, because I’m alive. To be a pessimist means you have agreed that human life is an academic matter, so I’m forced to be an optimist. I’m forced to believe that we can survive whatever we must survive.” (Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro 108)

The act of living, in itself, is a statement of optimism. To live and to not just value your fellow man, but to truly love them, to want what is best for them, not because they are black or white, but because they are human and that they are worthy of the same love that brought yourself into being may be a radical and idealistic notion. But it is one that Baldwin stood by firmly and it is one that he fought for until his dying breath in 1987.

And so on this 100th celebration of this radical witness to history, it is up to us, not as Americans, but as fellow citizens on this earth to live up to the creed that James Baldwin devoted his life’s work. In the 2020s, that goal may seem out of reach in the scope of our lifetime. But as Jimmy once said, “not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced” (Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro 103).

Socials:

Substack: bryceallenreads.substack.com

Twitter: twitter.com/bryceallenreads

Threads: threads.net/@bryceallenreads

Glasp: glasp.co/#/bryceallen

For more articles on reading, writing, and the creative process, subscribe to my free Substack newsletter!

You can support my writing by buying me a coffee!

You can also show support by purchasing from the affiliate links in this article.

Sources:

Baldwin, James. I Am Not Your Negro. Directed by Raoul Peck, Vintage International, 2017.

Baldwin, James. The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948–1985. 1985. Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, Beacon Press, 2021.